- #UPGRADE LIGHTWRIGHT 5 TO LIGHTWRIGHT 6 ONLINE HOW TO#

- #UPGRADE LIGHTWRIGHT 5 TO LIGHTWRIGHT 6 ONLINE SOFTWARE#

Next, I updated NYPL’s local Archivematica Format Policy Registry (FPR).

#UPGRADE LIGHTWRIGHT 5 TO LIGHTWRIGHT 6 ONLINE SOFTWARE#

Taking cues from a blog post by Jenny Mitcham at the University of York on creating a signature, and another by NYPL’s Head of Digital Preservation Nick Krabbenhoeft on using bash to help verify your signature hypotheses, I developed six separate signatures, one for the Show File format associated with each of the six Lightwright software versions.

#UPGRADE LIGHTWRIGHT 5 TO LIGHTWRIGHT 6 ONLINE HOW TO#

There are a number of great resources that detail how to create a file format signature for beginners. I decided to focus my efforts around the Show File format, as it represents the majority of files in the NYPL collections. Adding Lightwright signatures to PRONOM will help archivists at NYPL identify those formats in the future. NYPL uses a file profiling tool called DROID to process digital files, and this tool references the PRONOM registry. Developing a file format signatureĪt this point, I felt I was ready to begin developing file format signatures for submission to PRONOM. I was also fortunate to interview the developer, John McKernon, who provided further insight into the software’s history and system requirements, and information on some of the lesser-used file formats. Beginning with the website and user manuals, I established a list of the different software versions, and their release dates, programming languages, and system requirements, as well as their associated file formats.

The next step in my process was to fill these gaps through further research and contribution to the aforementioned registries. There were no entries in either PRONOM or the Archivematica FPR, and the information recorded in Wikidata and Wikipedia was incomplete.

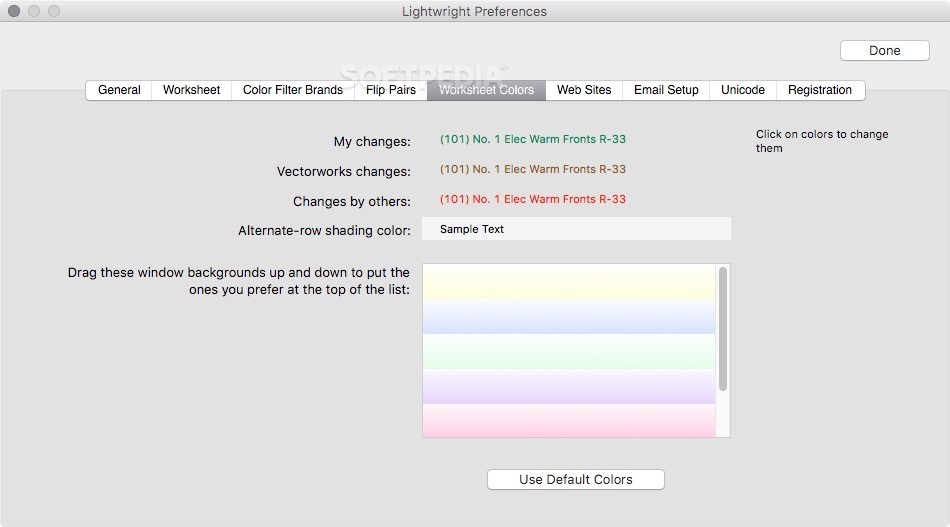

My research led me to examine three registries:Īrchivematica’s Format Policy Registry (FPR)Īside from the website maintained by the developer of Lightwright, there was very little information available on the software and its file formats. In particular, I focused on registries that aggregate technical information about software products, their support lifecycles and requirements, and the file formats each product can read and write. The first step in my work was to map out the current preservation environment for the Lightwright software, and identify any gaps present in the resources developed by the digital preservation community. Currently, six of these formats are represented in three separate collections at NYPL: the Tharon Musser designs and papers, the Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer papers and designs, and the Merce Cunningham Foundation records. Since the debut of Lightwright in 1988, six versions of the software have been released, resulting in more than 15 associated file formats. It combines a relational database with a graphical user interface that allows users to create lighting designs and related paperwork. Lightwright is a software that is widely used by lighting designers and production staff to manage theatrical lighting for plays and musicals, dance performances, and other live events. Screenshot of Lightwright Version 5 (demo) GUI My project during the spring semester has been centered around one such group of files-those produced by the proprietary Lightwright software. However, there are several collections held by the Library for the Performing Arts that contain unique file formats, which are dependent on their native software to be read, and whose preservation and access needs require further definition than more common format types. These formats have specific needs in terms of preservation and access, but because they are commonly associated with archival collections, the digital preservation community has established a set of processes and best practices for caring for them. During my second semester as the Pratt Digital Preservation & Archives Fellow, I’ve been working with Digital Archivist Susan Malsbury in the Archives Unit of Special Collections, to tackle issues surrounding software preservation.Īs a graduate student, when I think about digital archiving-especially in the context of the performing arts-I tend to think about audiovisual recordings, images, and ephemera, and the challenges surrounding their associated file formats (MOV, WAV, TIFF, etc.).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)